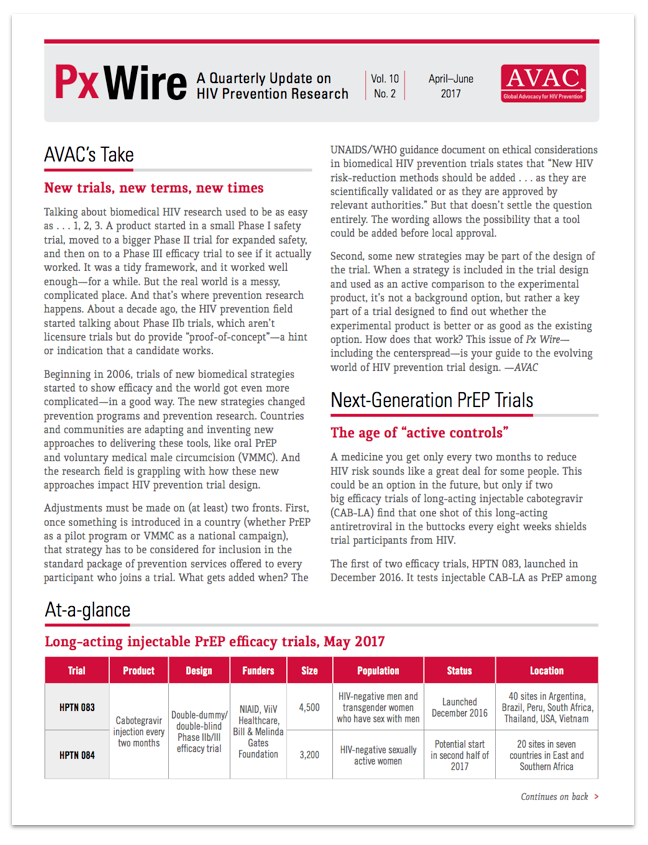

Px Wire April-June 2017, Vol. 10, No. 2

This issue of Px Wire, AVAC’s quarterly update on HIV prevention research, offers an advocate’s guide to some new types of biomedical prevention trial designs. You’ll find a summary of long-acting PrEP trials, a lexicon of key terms for the “post-placebo era”, and a handy illustration for looking smart while you explain “double-dummy double-blind”.

Was this content helpful?

Tell us how we can improve the content.

Was this content helpful?

Thank you for your feedback!